I got my dark sunglasses,

I got for good luck my black tooth.

I got my dark sunglasses,

I'm carryin' for good luck my black tooth.

Don't ask me nothin' about nothin',

I just might tell you the truth.

--Bob Dylan, Outlaw Blues

I want to publicly thank

The Viscount for two things.

First, to help me through my convalescence he very kindly sent me a copy of

John Lennon: Imagine, the 1988 film directed by Andrew Solt. Peace on you, brother.

And second, watching that film just now has presented me the Royal Road to explore something that's been on my mind for some time now. Back in late May, the NRO posted a list of what they were pleased to call

"The Top 50 Conservative Rock Songs of All Time." The list was quite risible, ripping songs quite out of context, taking as literal lines obviously intended ironically, and declaring sentiments expressed in the lyrics

conservative on the most laughably absurd pretexts.

This list made me (and quite a few others) guffaw uproariously (and attracted Pete Townshend to come slumming in Lower Left Blogovia, to judge from comments he left with

Blue Girl, Tom Watson and

Lance Mannion). But it also set my brain a-ponderin': How can the right-wing mind be so utterly unconscious of irony as to lay claim to large swathes of music that is in every detail of its makeup patently, avowedly, and dedicatedly contrary to their world view, and shake their tightly clenched fannies to it?

That's not your music, the mind shrieks.

Get your goddamned meathooks off it.Partly, of course, the violence that's been done to Our Music by corporate cooptation has drained much of its original force. (That this cooptation has been done largely with in cahoots with the original artists is only more depressing.) I remember staring in mute horror at a television screen sometime in the late Eighties as the Beatles' single version of "Revolution" was employed to engender positive feelings toward Nike footwear in my lizard-brain. The daily insults to meaning in the "repurposing" of rock songs in commercials have the cumulative effect of deadening the listener's mind to any sort of passion this music may once have lit. If a sun-splashed Caribbean Cruise spot can be edited to the rhythms of "Lust for Life," Iggy Pop's anthem to kicking heroin, then

fuck it. Nothing means anything anymore.

But it once meant something. And that

something is what we reflexively spring to defend when NRO stakes its grotesque claim.

And what was that

something?In the

Imagine film, we are given a fascinating interchange between Lennon and Yoko (and a claque of admirers) and the liberal-turned-Silent-Majority-spokesman cartoonist Al Capp, at the Lennons' Montreal Bed-In in June of 1969.

(Click to watch in a new window.) Both sides are quite obviously intensely aware that they are actors playing to ubiquitous and intrusive cameras in a staged media event, as they present their chosen roles in a set-piece that recapitulates the passionate intensity of the times.

I won't defend Lennon in this clip. He comes off as petulant and defensive, and seems a bit surprised when Capp attempts to score cheap points off vulnerabilities that a more prepared and thick-skinned public figure would have had easy (and funny) ripostes for.

But even less defensible are those cheap shots on Capp's part. Capp made his living not only as a cartoonist at the time but also as a radio commentator and campus speaker railing against the antiwar movement, portraying them as unkempt dangers to suburban workadaddy values, flouters of the eternal verities of home and hearth, hairy and disgusting trolls whose interest was not in ending a war but in the wholesale destruction of a treasured way of life. Watch Capp with this notion in mind, and his motivations become clear: His flaunting of the nude photos from the cover of

Two Virgins is not an attempt at exposing some inconsistency in Lennon's antiwar argument, but simply to tar John and Yoko as sexual perverts, and render them thus

ipso facto dismissable. (The fact that Capp was charged with the attempted rape of a female student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison a year later, with similar allegations from at least four other campuses, makes this innuendo on his part even more nauseating.)

Does any of Capp's scapegoating sound familiar? Let's see how the GLBT folks, undocumented workers, flag-burners -- and, naturally, their

defenders, feel about it!

Lennon, in a time when artists and activists reached for the Dada values of shock and black humor in the service of awakening bourgeois apathy -- a time, that is, when levitating the Pentagon and

other deliberately insane acts seemed to make perfect sense in a war-hungry country gone mad -- made a conscious decision to play the public Holy Fool to promote an unarguably laudable cause. Whatever you may think of Lennon's public antics at the time (and some of them, let's be honest, were downright embarrassing -- "imagine no possessions" coming from one of the world's richest men!) you can't argue with their sincerity.

But Lennon's Holy Foolery didn't just spring fully formed from his forehead one day in 1968. To play the Holy Fool to inspire human liberation is to embody absolutely the

single founding principle of rock-and-roll. To stand in front of an audience with a weird haircut and a loud guitar, wiggle your hips and go

WAAAAAAAAH! into a microphone: how does that differ in any material way from trying to levitate the Pentagon? The two acts may differ in quality but they communicate exactly the same message:

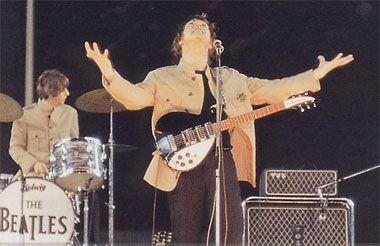

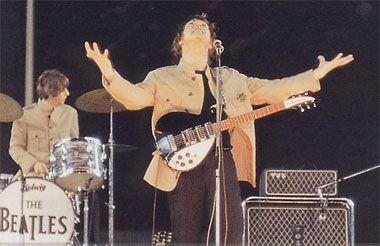

free yourself! The man who sat in bed in Montreal and allowed himself to be called a pervert by a neanderthal rapist is exactly the same man who, some three years before, stood in front of a screaming crowd of teenyboppers in Shea Stadium playing electric organ with his elbows, laughing to the point of tears at the glorious absurdity of the situation.

(Seriously. Watch it, especially Lennon. Best Beatles Live Performance Ever.)This, then, is what we rush to defend as our own. This is what they must never be allowed to take away: Rock and roll

frees your ass. To attempt to enlist the Holy Fool, the jibbering maniac with the guitar and the haircut, in the service of a cramped and crabbed and ugly ideology shows that you don't understand rock and roll. What's more, you will

never understand it.

You might hear the beat, you might tap your toes -- but there is a jagged, bleeding hole in your mind. Go back with Al Capp, where you belong, and equate John and Yoko's Holy-Fool honesty -- their

nudity, if you must -- with turpitude. You know you will, in the end. You always do.

You'd have to have been living under a rock this last week to have missed the blogspherical uproar over the publication of the list of "Top 50 Conservative Songs," compiled by John J. Miller at

You'd have to have been living under a rock this last week to have missed the blogspherical uproar over the publication of the list of "Top 50 Conservative Songs," compiled by John J. Miller at