There was a good discussion about Prog Rock over at Kevin Wolf's place last week. In the comments I allowed as how I thought the adjective "progressive" was largely bullshit, a nonexistent category. I also dislike the term because it implies that only music so labeled can cause music to "progress" -- whatever that means -- and anything not dubbed "progressive" is "regressive" or perhaps "reactionary." I'd also add that when popular music has progressed -- if we define it as undergoing a recognizable metamorphosis from one genre to another, like from jump blues to rock-and-roll, or from rock steady to reggae -- it certainly wasn't self-proclaimed "progressive" musicians who provided the impetus. Those changes are organic, they come from within a musical school, and not from some hothouse laboratory, some Kollege of Musical Knowledge. They come from growth, which is not the same thing as increased complexity.

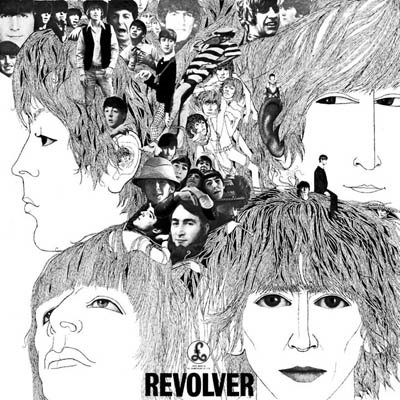

Forty years ago today, on August 6, 1966, Revolver was unleashed on an unsuspecting -- and remarkably unprepared -- world. It's not been the been the same place since.

Sergeant Pepper is credited with being the first self-consciously integrated rock album -- never mind that the "concept" of the record is actually quite thin: A fictional band concert provides a framing device for the goings-on, and that's pretty much it. (Others have pointed out that it isn't really even the first "concept album"; a good case can be made for The Mothers' Freak Out! and for Dylan's Blonde on Blonde, both of which predate Pepper by at least six months. Nearly as good a case can be made for Frank Sinatra's Songs for Swingin' Lovers!) The songs on Pepper don't comment on or elucidate each other, they don't share a common theme or subject matter, and the album doesn't progress (that word again!) from one point to another -- it doesn't really tell a story.

Revolver, on the other hand, does all of these things. If Rubber Soul, from late 1965, marked the moment that the Beatles began to see the world through the eyes of adults, then Revolver gives us the world as seen by adults who know they are going to die. Death is everywhere on this record -- from Eleanor Rigby's terribly sad, lonely and meaningless end (redeemed only by the accidental intercession of another pathetic character, Father Mackenzie, and made bearable by George Martin's achingly beautiful and empathetic string arrangement) to Lennon's obsession with druggy oblivion in three of his contributions: "I'm Only Sleeping," "She Said, She Said," and "Tomorrow Never Knows." Even "Taxman" has sardonic advice "for those who die."

But if Revolver acknowledges the inevitability of death, the album as a whole resoundingly rejects nihilism. It offers solace in adult romantic love, in psychedelic insight, in the innocence of childhood, and a healthy dose of Doctor Robert's cynicism. The album shows clearly the extent to which not only Harrison but all of the Beatles had internalized the Eastern insight, sympathetic with their own psychedelic explorations, that life is illusory, an extended dream. Lennon's persona in "Rain" (technically not on Revolver but very much a part of it -- even a key to understanding the Beatles' mindset in 1966) asks the vitally important question:

Can you hear meIf you listen carefully to a collection from Revolver's period like Rhino's Nuggets II: Original Artyfacts From The British Empire & Beyond, it becomes immediately apparent how astonishingly divisive the psychedelic experience was in the mid-Sixties. I haven't done a careful count, but an amazing number of the delicious obscurities in that collection set up an "us-and-them" division -- "us" being those who've had their eyes opened by LSD and "them" being the Squares who haven't. If the eye-opening experience of acid is that life (and, indeed, death) is a series of "states of mind," none of which is more valid or more "real" than any other, then it follows naturally that, as in "Rain," the Squares need to have their eyes opened as well.

That when it rains and shines

It's just a state of mind?

But it's Revolver's crowning achievement that it rejects this then-fashionable division in favor of universality. The abject Eleanor Rigby and the hopeless Father Mackenzie feeling his faith dying, these are not people who going to be "saved" by an impregnated sugar-cube -- these are desperate people in need of human compassion. The miserably depressed lover of "For No One," the fragmenting mind, desperate for the innocence of childhood, of "She Said, She Said" -- no glib oh-wow-man insight will work miracles for these people. The "state of mind" of these damaged individuals is far, far more complicated than "rain or shine," and the Beatles were immeasurably compassionate -- adult -- to present them to us in the painfully divided year of 1966.

The songwriting is absolutely masterful on this record. I can't but stand agape in awe of the technical prowess of "Here, There and Everywhere," in particular. The first verse concerns itself with "here"; the second with "there." On the word "everywhere," the song suddenly flowers outward, exploring a new key area, a new instrumental texture. For the rest of the song, the words "there" and "everywhere" serve as hinges to change from the home key to the key of the bridge and back again. A humble device, simplistic, even, but its execution is devastatingly deft. It can't be said enough: This assured and mature songcraft came from a young man who, less than three years before, had written "Hold Me Tight" -- a fine little rocker, one I'd be happy to play in a band -- but in formal layout and harmonic structure trite, trite, trite.

Progression in music is not a matter of more. To view progress as a question of more notes-per-beat, more incoherent harmonic complexity, more mathematically improbable time signatures, is to do violence to the central point of music, which is to draw us together. Revolver stands in its humane universal inclusiveness at the edge of a precipice, just before the world became irrevocably atomized, shattered, shredded by history. We still haven't put the pieces back together.

I fear we never will.

15 comments:

BTW whoever the fuck stole my vinyl copy of Revolver should be tried at the Hague -- just sayin'

The man in the mac said, "You gotta go back," you know he didn't even give us a chance.

Christ, you know it ain't easy...

Father MacKenzie - the man in the mac?

Progress, as you say, doesn't necessarily involve complexity, or even novelty. All it takes is a Lennon/McCartney or Mozart or Michelangelo or Shakespeare...

Well, IMHO, the problem lies not with the music, but with the labels we apply to it. When Yes comes out with "Awaken" in 11/8, it's pretentious and overblown; Ornette Coleman or Igor Stravinsky are pioneers for exploring the same territory.

Is "Awaken" progressive? Is it "rock"? When we see guitar, bass, keyboards, drums and vocals, do we label that as "rock" without considering the music being played? When ELP records Alberto Ginastera's Piano Concerto, is it rock? What about Ludacris "Coming 2 America" from Word of Mouf - containing Mozart's "Requiem", 3rd movement (Dies irae) and Antonín Dvořák's Symphony No. 9, "From the New World", 4th movement (Allegro con fuoco)? (I can't even begin to imagine what label we might apply to that...)

Keith Emerson was once quoted as saying (regarding the Allman Brothers band, I think) "We could jam with them, but they couldn't jam with us." Height of arrogance or recognition that they are speaking different languages of music? Does anyone doubt that Duane Allman could have played like Segovia if he chose to do so?

There are true virtuosi who chose to speak in the idiom of rock. Duane Allman is one, Keith Emerson is another. Baudelaire is gibberish if you don't speak French, n'est-ce pas? Beethoven didn't limit himself to symphonies, Mozart wrote concerti and opera. Frank Zappa covered the waterfront, from cheesy do-wop hommage (Lucille has messed my mind up) to Spike Jones influenced comedy (Live at Fillmore East). And then Pierre Boulez commissioned Frank to compose some 12-tone pieces for his chamber ensemble. We're gonna need a bigger box of labels!

I get a kick out of Yes and Chuck Berry and the Beatles and Stravinsky and Holst, and the Beach Boys and the Pogues, and Dire Straits and Nils Lofgren and the list goes on and on. They're all working with the same 88 (or so)notes, just like the writer for the high school yearbook is working from the same dictionary as Salinger or Updike.

It's about quality, as Robert Pirsig suggested in "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" and elsewhere. And quality is like obscenity; we all know it when we hear it. Furthermore, we recognize its absence when it's not there.

Good post, Jeddie. I love it when you write about music. You have a gift for it.

I wish I could, but I don't have the *words.* I have the *feelings* (of course, goopy me), but not the words.

I get a kick out of Yes and Chuck Berry and the Beatles and Stravinsky and Holst, and the Beach Boys and the Pogues, and Dire Straits and Nils Lofgren and the list goes on and on. They're all working with the same 88 (or so)notes, just like the writer for the high school yearbook is working from the same dictionary as Salinger or Updike.

Great thought.

I think roxtar said better what I was trying to say in my post where, when seeing that I'm once again failing to get my point across, I inevitably reach for my Duke Ellington reference. Which only seems to mirror roxtar's thinking.

And, yeah, Zappa's Fillmore East is a wonder.

Ned, I agree with your analysis not soley because it convinces but because I've experienced it myself.

I was 7 years old when Sgt Pepper's appeared and the word from everybody was essentially that it was the great rock album ever and no one would be able to top it. Lenny Bernstein as much as said so.

But as I got older, and began to listen to the Beatles with my own ears, Revolver became, for me, the greatest Beatles album. I didn't know why exactly, but I think you confirm here what was latent in my thinking about their music.

A loyal if lazy reader reporting in. I agree that your music entries are great.

The progressive rock tag was relevent for a few years in the 60s as a new attitude and form was defined apart from good ol' Top 40 radio. By the early 70's it had become a horrible cliche like MOR. Now, it is assigned to a niche only. Fortunately, that niche is one I choose to avoid so it helps when this label is used for me. The Beatles are so much more than progressive though. Zappa is not progressive in my humble mind.

Somewhat off thread, but since "Zen and the Art" has been mentioned, I thought I'd point y'all to an interview with Robert Pirsig on the occasion of the reissuance of Lila I ran across yesterday...

Is the second side of Abbey Road the first through-composed album side?

Tull did Thick as a Brick through-composed on both sides, but that was three or four years later?

Keith Emerson is a chowder head.

You sure dance about architecture good.

I'm on a pretty dilettantish level concerning The Fab Four and Rock criticism, but I happened (Thanks, Serendipity!) on a broadcast over WGBH of a rockumentary called Everything Was Right: The Beatles' Revolver produced by Paul Ingles and distributed by PRI. Perhaps coming to an NPR station near you, or it will be available on the net after November 30. Anyway the link has commentaries and interviews about the tracks on Revolver that were interesting to a novice like me and touch on the innovations of the album and reasons for its current popularity. Hey, I didn't know the title referred not to a handgun but to a spinning vinyl disc.

I would say that had I never heard the album this post would have made a believer out of me. Excellent.

Still, "dancing about architecture" applies here to me, and me alone. For pure listening pleasure I still prefer:

Abbey Road

Rubber Soul

A Hard Day's Night

The Beatles

all consistenly over this one, but I can't explain why. I love most of the songs and like all the rest, am fully aware of their innovative use of the studio, (first record after they retired from the road,) all of it.

It just doesn't ring with me the way it does for most, and while I understand the fascination with the intelligence behind "Here, There and Everywhere," the song doesn't feel good to me. The feelings expressed sound calculated. I much prefer "For No One" and "Good Day Sunshine" as representations of Paul's work from that time period.

And, I think it is pretentious and arrogant for Keith Emerson to believe ELP was somehow superior to The Allman Brothers because he had a classical background. ELP's interpretation of Mussorgsky's and (later) Ravel's sublime "Pictures at an Exhibiton" is one of the worst acts of desecration against a classic that I've ever heard. In contrast to that, Duane Allman did justice to Miles Davis' "Kind Of Blue" by modeling the Allman's jamming style after hours and hours of studying that recording.

Defending the unpopular is what I do, so a few words in defense of keith Emerson. However politically incorrect his remarks about the Allman Brothers may have been, I am open to the interpretation that recognizes the difference in the two idioms; if your language is blues, you know exactly what comes after:

"I gave you a brand new Ford

and you just said I want a Cadillac

I bought you a ten dollar dinner

You said Thanks for the snack

I let you live in my penthouse

You said it was just a shack....."

I don't think Keith Emerson would miss the cue, but I guess it's possible.

But if you are classically schooled, the counterpoint in a fugue will come to you as a result of your training just as "I gave you seven children, and now you want to give them back" would come to any blues player.

Shit, I dig 'em both. Listen to the Layla album and tell me Duane didn't eat Clapton for lunch.

And I still get a kick out of ELP's version of "Pictures at an Exhibition", pretentious and self-indulgent as it is. I also like Spinal Tap's mockery of such pretense by inserting 8 or 10 bars of Boccherini's Minuet from the String Quintet in E Maj. in the bridge of "Heavy Duty."

Hey, it's all good. Except when it isn't. (Yeah, J-Lo, I'm lookin' atchoo!)

There are a number of milestones in modern music where something new comes out and everyone says "What is that?" Is it rock? Jazz/rock? Progressive? Just what the hell is it?

While I love Revolver, Sgt. Pepper was more one of those moments. Maybe Joni Mitchells "For The Roses" or "Mingus" or.... (I'm a huge Joni fan). Steely Dan's "The Royal Scam"? Miles' "Bitches Brew"? Paul Simon's "Graceland"?

Lately, Sufjan Stevens has given me some "what is that?" moments. Check out his "Illinois" or "Michigan" albums.

Great story: my daughter is 12, and a Pink Floyd fan, specifically "Dark Side of the Moon." The other night our local public television station showed the part of the "Pulse" concert where they play the enire DSOTM. Visually, it's just stunning. She and I are snuggled on the couch, when, in an amazing tableau of light and color and sound, David Gilmour sings:

Far away across the fields,

The tolling of the island bell

Calls the faithful to their knees,

To hear the softly spoken magic spell

My daughter said "I feel like crying all of a sudden; isn't that weird?"

No darlin', not weird, not even a little bit. She didn't know what It was, but she knew quality when she saw it.

The "state of mind" of these damaged individuals is far, far more complicated than "rain or shine," and the Beatles were immeasurably compassionate -- adult -- to present them to us in the painfully divided year of 1966.

Funny, that choice of words -- I remember thinking years ago that what America needed was not a Moral Majority movement (with its attendant simplistic absolutism, homophobia, gynophobia, fetus worship, etc.) but a Moral Maturity movement -- an ethics of responsibility for complex adults in a complex world where most things come in shades of gray.

Then I realized that the movement we needed was on our shoulders, so to speak.

--nashtbrutusandshort

Categorical Aperitif

Post a Comment